Over the past couple of years, the surge in inflation has had a huge impact on markets and economies around the world.

The rate of inflation is now falling back from those record highs, but the progress has been quite slow and headline rates remain higher than central bank targets.

The initial surge in prices can, in part, be traced back to the Covid-19 pandemic, the disruption this caused to the global economy, and the huge amount of stimulus pumped into the financial system.

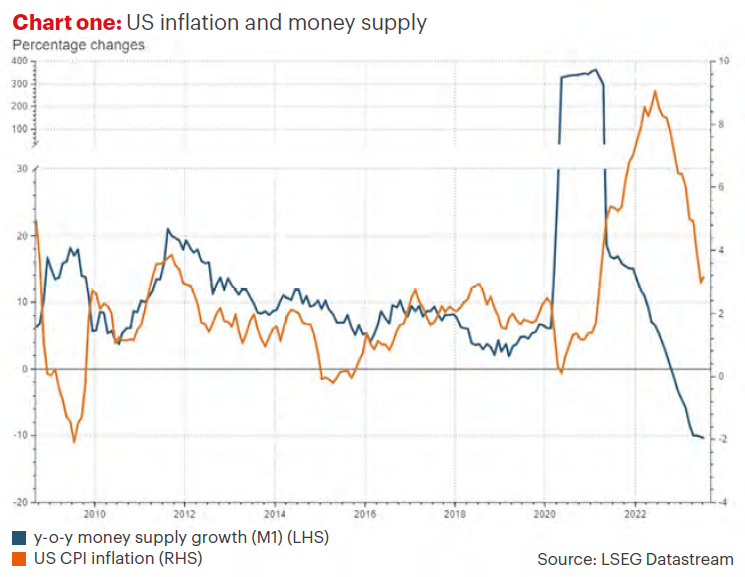

For example, chart one shows the year-on-year change in the US money supply (the amount of money in the financial system – blue line – left-hand scale) compared to US inflation (orange line – right-hand scale) over the past 15 years.

As you can see, the two lines often follow broadly similar paths. There was a huge increase in money supply in 2020 (the chart axis has even had to be curtailed to fit it on), followed by a spike in inflation shortly afterwards. Money supply is now shrinking so might prices follow?

Is this just a relatively temporary surge in prices or a change in a longer-term trend?

Market expectations and potential returns

Each year we carry out detailed research into the long-term expected returns of various asset classes. Once we have done this, we can work out what mix of assets might give us the best chance of achieving our targets of beating inflation by various amounts (depending on the portfolio).

To do this, we also need to make an estimate of what inflation might be. For this, we take a “wisdom of the crowd approach” and assume that inflation will be in line with market expectations.

Currently, markets are pricing inflation in the US at around 2.5% for the next 10 years.

In the UK, the market expectations for RPI (retail prices index) are around 3.5% for the next decade.

RPI is used even though it is not considered a reliable statistic anymore, as this is what most index-linked bonds are based on. Typically, RPI has been perhaps 1% higher than the official CPI (consumer prices index) inflation figures, so we can say markets might expect around 2.5% in the UK as well.(1) As an aside, our findings for potential future returns look incredibly positive. For example, investment-grade corporate bonds currently yield 6.25% (3.75% above expected inflation) and high-yield bonds look even better at 7.5% yield (5% above inflation), also over the same term.

We would expect a typical portfolio of global equities to return around 9.5% p.a. (7% above expected inflation) based on various valuation metrics such as price/earnings, which have been good indicators of returns in the past.(2) We therefore think we could see some attractive real returns going forward.

If markets are right, then inflation will be somewhat higher than it was over the last 10 years or so, prior to the recent spike.

The key question, however, is whether the market is right? Might inflation be markedly higher (or lower) than expected and what implications would this have?

What might cause a change in long-term inflation trends?

De-globalisation & demographics

One of the key drivers of economic growth and inflation will always be demographics.

To increase economic growth, either output per worker needs to increase (being more efficient) or the number of workers needs to increase.

However, we know that populations in developed countries are generally ageing. In 1990, the ratio of old-age to working-age population was 20% in OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation & Development) countries. By 2000, this had increased to 30.4%. By 2050, this will likely increase to 52.7% of population.3 Given this, unless we become significantly more productive (which is possible!), then economic growth is likely to slow.

There is typically a strong link between economic growth and inflation. Often, we get inflation when economies are growing strongly, and we get lower inflation during downturns.

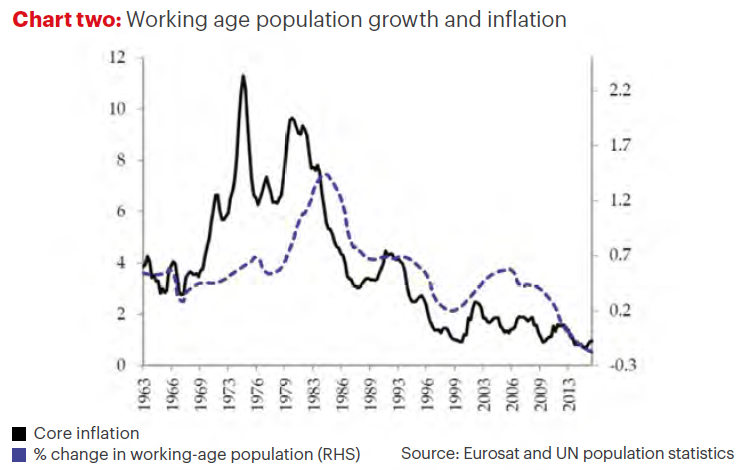

An ECB working paper from 2017 found a strong relationship between working-age population growth and inflation, as illustrated in chart two.

But according to others, these demographic changes could in fact be inflationary.(4)

In their book “The Great Demographic Reversal,” Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan argue that de-globalisation and ageing populations will cause prices to increase.

Their argument is that low inflation from the previous two decades has been largely caused by China’s rise as an economic superpower. As China became more integrated into the global economy, cheap Chinese manufacturing has reduced the prices of many goods that we buy.

This was aided by the trend for Chinese rural workers to move to the cities and essentially join the global workforce, offsetting the declines in the West.

However, China now has its own demographic issues. Largely as a result of its past “one-child” policy, the supply of rural workers has been pretty much exhausted, so this trend may well have ended.

In addition, as relations between China and the West become more strained, there are efforts on both sides to reduce economic integration and increase self-sufficiency. This could be inflationary as manufacturing goods in the US or Europe (for example), typically still costs more than doing so in China.

Goodhart & Pradhan also argue that an ageing population in the West could in itself be inflationary, contrary to the ECB’s findings, largely because older populations need to spend more on health care.

Technology & climate change

However, there are two other long-term trends which could make a big difference to inflation.

The first is artificial intelligence (AI). According to a recent report by PwC, progressive advances in AI will increase the global GDP by up to 14% between now and 2030 (5) (see related article Artificial Intelligence: Killer app?). Goldman Sachs believe this could account for an increase in productivity growth of 1.5% p.a.(6)

If they are right, this could offset some of the concerns about the shrinking workforce, by effectively replacing them with “robot” workers. This should in theory be deflationary as this means companies can produce their products more efficiently and keep prices lower.

The other trend is climate change, which could have a significant impact, both directly and indirectly.

Direct effects might include the impact of a warmer planet on food production which may then lead to price increases. It could also lead to population migration from hotter to cooler climates.

The indirect effects would include the costs of de-carbonising the economy.

This will require heavy investment in renewable energy, smart power grids and battery storage, changes to how we heat our homes and offices, electric car infrastructure and so on.

All this could lead to higher energy prices during the transition, for example.

However, on the other hand, this could be deflationary in the long term. Solar and wind energy is already cheaper to produce than energy from fossil fuels (7) and is becoming more efficient all the time. If we can solve the “reliability” problem through energy storage, then we could end up with very cheap energy – after all, the sun and the wind come for free!

Summary

We subscribe to the view that inflation might be, on average, somewhat higher than the central banks would like in the next few years (though it could be volatile), because of issues like de-globalisation and spending on climate transition.

But longer term, we think efficiencies from technology, AI and renewable energy could help keep prices down. Ageing populations are still more likely to reduce inflation than increase it.

Given all the competing trends, the outlook is far from certain. Fortunately, from an investment point of view, we are able to hedge our bets.

For example, many of the trends I’ve mentioned in this piece are also trends we can benefit from in portfolios.

We already invest in areas like clean energy, technology, and healthcare stocks. We invest in emerging markets outside China (such as India) which have more favourable demographics that may help drive their growth.

And crucially, many of these asset classes may help us hedge against potentially higher inflation. If there are price increases in these sectors, then this means revenues for companies in these sectors will likely increase too.

Inflation will always be one of the biggest concerns for any saver, but investing over the long term gives us a particularly good chance of achieving returns over and above the increase in the cost of living.

Past performance is for illustrative purposes only and cannot be guaranteed to apply in the future.

This article is intended as an information piece and does not constitute a solicitation of investment advice.

If you have any further questions, please don’t hesitate to contact us. If you’re a client you can reach us on 0161 486 2250 or by getting in touch with your usual Equilibrium contact. For all new enquiries please call 0161 383 3335.

Sources

(1) Refinitiv Datastream, based on 5yr/5yr inflation swaps.

(2) Datastream / Equilibrium Investment Management – Long Term Investment Assumptions Sep 2023.

(3) Demographic old-age to working-age ratio | Pensions at a Glance 2021 : OECD and G20 Indicators | OECD iLibrary (oecd-ilibrary.org)

(4) Demographic and inflation (europa.eu) ECB “Demographics & Inflation, 2017“

(5) PwC: AI analysis sizing the prize report (pwc.com)

(6) Generative AI Could Raise Global GDP by 7% (goldmansachs.com)

(7) Renewables: Cheapest form of power | United Nations