An interesting decision

This month, the Bank of England surprised markets by failing to put up interest rates.

The reason it was such as surprise was because several officials had gone out of their way to signal to markets that rates were due to go up shortly, in the face of rising inflation.

On 17 October, the Bank of England’s governor, Andrew Bailey, said:

“Monetary policy cannot solve supply-side problems – but it will have to act and must do so if we see a risk, particularly to medium-term inflation and to medium-term inflation expectations.”

“And that’s why we at the Bank of England have signalled, and this is another such signal, that we will have to act,” he said.

This sent a clear message to bond investors, who sold UK governments bonds as a result.

However, when it came to the November’s meeting, the members of the Monetary Policy Committee voted 7-2 in favour of keeping rates on hold. Given what he had said a few weeks earlier, it was surprising that the governor was amongst those voting for no change.

The Bank, of course, has an official inflation target of 2% p.a., and their key role is to try to maintain prices within 1% of this figure.

So, why have they kept rates on hold, given the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation is currently above 3%, and predicted to go as high as 5% next year?

Bailey himself said that monetary policy cannot solve supply-side problems. As we’ve been saying for a while, inflation is being driven by an imbalance between supply and demand.

As economies re-open, demand has gone back to pre-pandemic levels in many cases, in some cases higher. However, supply chains are still being hit by issues from several months ago, such as shipping and energy.

Putting up interest rates might dampen excess demand, but the inflation is being caused by a shortage of supply, which rates can do nothing about.

Temporary-Ish

We have been saying for some time we think the inflation is caused by temporary issues. We still think that, although they have certainly proved to be less temporary than we originally thought!

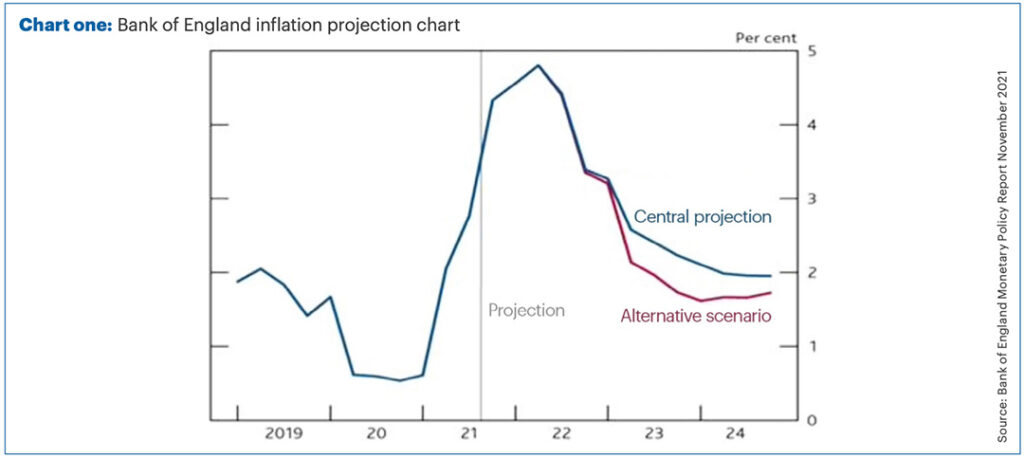

Chart one (below) shows the Bank of England’s projection for how inflation will change over time. The blue line is their central projection, which shows CPI nearing 5% next year, before falling back to 2% by the end of 2024.

However, it is possible that inflation could fall back quicker than this, as illustrated by the red line, where inflation drops below 2% by the end of 2023. We believe this may be a more realistic scenario.

We all know that energy prices have increased dramatically recently. A variety of factors have caused an increase in demand for gas (such as low wind speeds reducing the effectiveness of wind power this year), with supply hit by pandemic-delayed pipeline maintenance.

Gas and electricity are traded on exchanges, just like many other commodities. In particular, there is a large market for futures contracts, where investors can lock in gas at a particular price for a fixed point in the future. The futures markets also give us some ideas of how traders think the price of the commodity will move in the future.

We think there is a strange convention in the Bank’s inflation forecasts in that they will assume energy prices follow the futures market prices and after that, prices will remain static. In other words, the central projection (blue line) assumes energy prices remain high into perpetuity.

By comparison, the red line (Chart 1) shows what would happen if they ignored that convention and instead assumes energy prices will follow the futures market for the entire duration of the forecast.

If energy traders are correct about future prices (and there is no guarantee they will be), then inflation would drop back below the target much more quickly. Energy traders think the current high prices are temporary and will come down significantly.

There are also other signs that some supply chain issues are beginning to abate, with shipping rates starting to lower, along with some commodities. There is a potential time lag of 18 months before the impact of any interest rate hike is felt. If the Bank were to put up rates now, it may not have any effect until after inflation is already on its way down.

Disposable demand

The Bank also has a key role in keeping the UK economy steady. In his press conference, Bailey made the point that rising prices in themselves, combined with the increase in National Insurance, may mean that people’s disposable income is lower next year than this year.

Putting up rates too quickly or steeply could reduce disposable income even more, hitting demand for goods and services. They could be reducing demand just at the time that supply issues have sorted themselves out, slowing the economy more than required.

The Bank says they want to see more evidence that the economy is on an equal footing, especially as the furlough scheme has only recently ended, before putting up rates.

On the one hand, this makes total sense and putting up rates to control inflation at present is (at best) pointless in our view.

On the other hand, interest rates are still at the “emergency” levels of 0.1% – the record low from the depths of the pandemic. The economy could certainly stomach rates at 0.25%, and a gradual increase to 0.75% should not cause an issue, provided we don’t see an increase in unemployment, for example.

Whilst the Bank has not yet changed base rate, simply by talking about it they have already had some effect. For example, some of the cheaper mortgage deals were removed from the market in the run up to November’s meeting.

Meanwhile in the gilt market, despite selling off in the run up to the meeting, gilts have rallied sharply afterwards. Volatility in government bond markets is not particularly consistent with the Bank’s aim of “price stability.”

Central bankers should be careful what they say. So-called “forward guidance” can be a useful tool, but it only works if they retain credibility. Next time Bailey tries to give guidance to the market, investors may not be so willing to believe him!