This article is taken from our autumn 2022 edition of Equinox. You can view the full version here.

Over the centuries, our brains have evolved to become as efficient as possible, but do they help or hinder our decisions about money?

The realisation of having driven a familiar route, with no memory of the journey you just made, is one of the wondrous ways in which our energy-saving brains pilot our lives, without requiring much hard thinking.

Our subconscious brains use patterns stored from our prior driving experience to predict the actions we need to take.

They operate at a speed that is 20 times faster than conscious thinking.[1] They enable us to identify and make sense of relevant patterns in complex data, almost instantaneously. And, by deferring to them, they save us having to consume up to 50% more calories by thinking – in an organ that already consumes up to 30% of our daily calorie intake.[2]

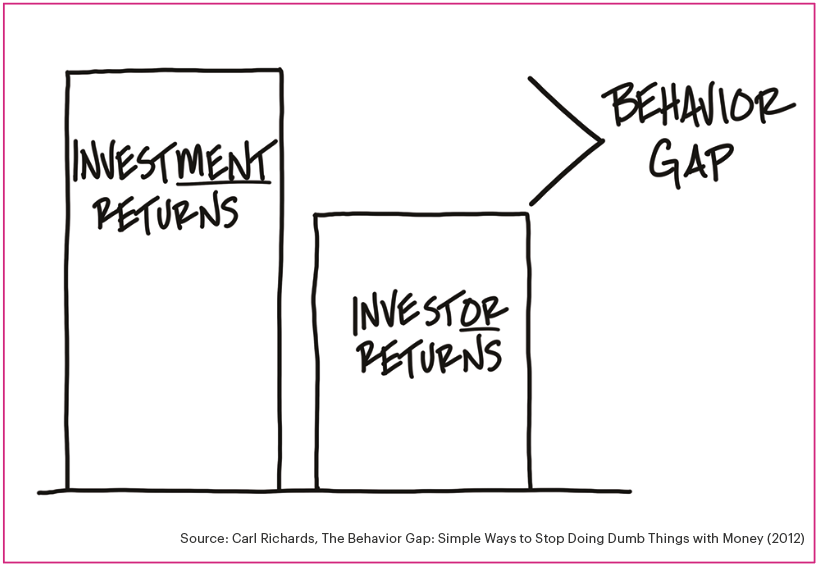

The origin of the behaviour gap in our wellbeing

That said, when our subconscious brains recognise the patterns contained in financial markets that are falling, they are frequently less helpful. Infused with stress and emotion, they all too often trigger us to sell when prices are low – before our high-energy thinking brains get the chance to consume the scarce calories required to override them.

Conversely, when stress takes the form of a fear of missing out, we are also inclined to overcommit to markets when prices are high.

And this battle for calories is one reason why a ‘Behaviour Gap’ has been typically found between the rate of return an investment produces over the long term, and the rate of return investors actually earn on that investment.[3]

Professor Steve Peters likens our emotional brain – which is one of the calorie-light agents of the subconscious ‘decision making’ that drives much of this behaviour – to a Chimp.[4]

Each of us has a Chimp. On constant alert for risk and opportunity, it evolved to do the heavy lifting of survival by telling us what situations we should approach and the ones we should avoid, before we get a chance to think rationally about them.

And therein lies the origin of the Behaviour Gap that can damage our wellbeing.

Once we experience an emotion, we tend to look for the information that rationalises its existence.

This means, how our Chimps feel about financial markets can become what ‘we’ think of them – which is how we may rob ourselves of the full rate of return that economies can provide, as we seek to shape the life we wish to live, look after those we love and leave a powerful legacy.

Managing our emotions to manage our wellbeing

There is a better way of approaching your finances with your energy-saving brain in mind. This involves accessing the part of your brain that mental health experts refer to as the ‘Observing Self.’

You can no more suppress a strong Chimp reaction to a dramatic financial event than you can stop a bruise from forming should you bang your head.

As a starting point to managing this inevitability, Peters suggests giving your Chimp a name. In my experience, you can go one step further and learn to notice how your Chimp is feeling, to put you back in touch with what your thinking brain understands of the situation, enabling you to plan and approach the future with appropriate confidence.

When you tell a doctor that you’re in pain and they ask you to score it on a scale of 1 to 10, it is your Observing Self that looks at the pain from the outside to find an answer.[5]

When you can laugh at your own ridiculousness, it is the Observing Self that inserts time and space between you and the experience, to see the humour in your folly.

And, in the heat of the moment, when your Chimp is telling you to flee from falling asset prices, or rush into an overheated market, it is your Observing Self that puts psychological distance between you and how you are feeling.

Critically, your Observing Self is not there to engage in a conversation about what it is seeing.

The Observing Self is there to sedate the Chimp, allowing you to access your thinking brain and plan as though ice itself is running through your veins.

For it is our high-energy, thinking brain, that enables us to appraise financial markets rationally and to look after our wellbeing: guided by reason and analysis, and now with full access to our problem-solving skills and memory for details.

In terms of managing behaviours and beliefs, which can sometimes lead to making poor financial decisions, we are now able to ask ourselves the golden Chimp management question and re-engage the power of our thinking brains:

This may be how I feel about financial markets, but what do I know about them?

We are aware that there is much for our Chimp-informed, pattern spotting, and energy-saving brains to fixate on in the current economy.

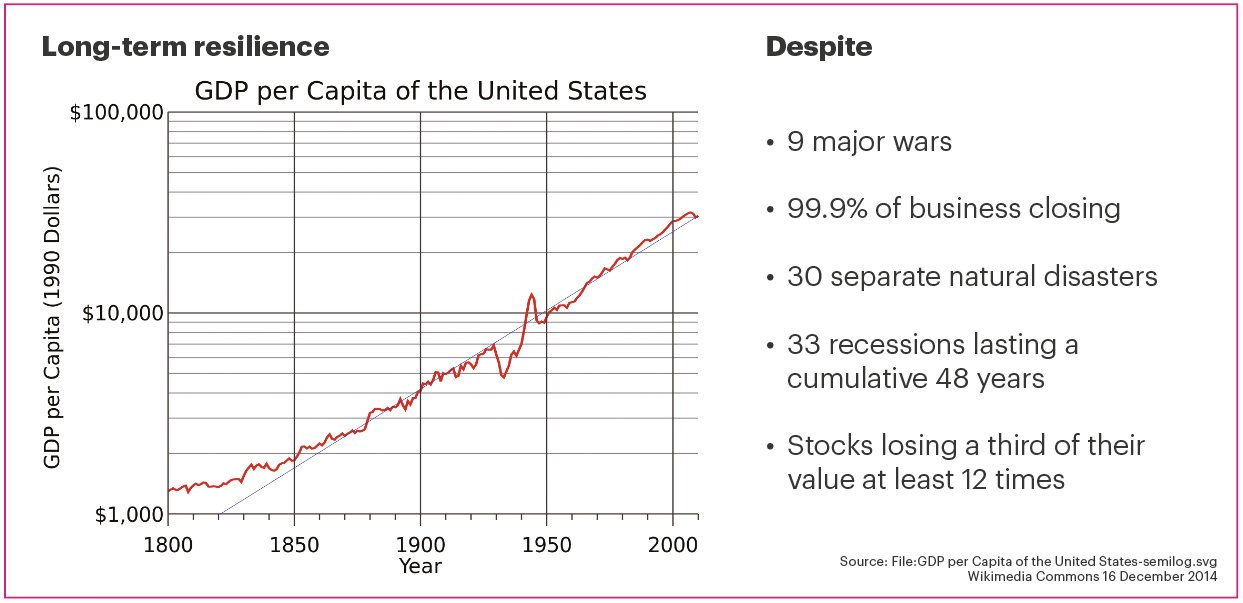

However, by observing those feelings, putting distance between ourselves and our emotions, and parking them, we can remind ourselves of at least three things we clearly know about markets that will never change 6:

- As seen in Figure two, economies are remarkably resilient to external shocks and setbacks

- Volatility is so normal that we should really frame it as the cost of admission to obtaining investment returns greater than simply cash and bonds

- Compounding is enormously powerful if given appropriate time to work. $81.5bn of Warren Buffett’s $84.5bn net worth came after his 65th birthday, because he had the peace of mind to stick with his investments, for example

Figure two: Economic resilience in US GDP per capita growth [6]

Past performance is for illustrative purposes only and cannot be guaranteed to apply in the future.

James O’Loughlin is the author of The Real Warren Buffett: Managing Capital, Leading People, and the founder and CEO of JOL Consulting, a firm that specialises in using insights from neuroscience to improve individual, group and company-wide performance on complex tasks.

Of the books referenced above, James recommends reading (first) The Chimp Paradox by Steve Peters and Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money.

Sources

- Prof Steve Peters, The Chimp Paradox: The Mind Management Programme to Help you Achieve Success, Confidence and Happiness, Vermilion, 2012

- Suzana Herculano-Houzel, The Human Advantage: A New Understanding of How Our Brain Became Remarkable, The MIT Press, 2016

- Carl Richards, The Behaviour Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things with Money, Portfolio Penguin, 2012

- Prof Steve Peters, ibid

- www.unk.com – 3 ways to activate your clients observing self

- Morgan Housel, The Psychology of Money: Timeless lessons on wealth, greed, and happiness, Harriman House, 2021