This article is taken from our spring 2020 edition of Equinox. You can view the full version here.

It sounds great – like an autopilot for your investments.

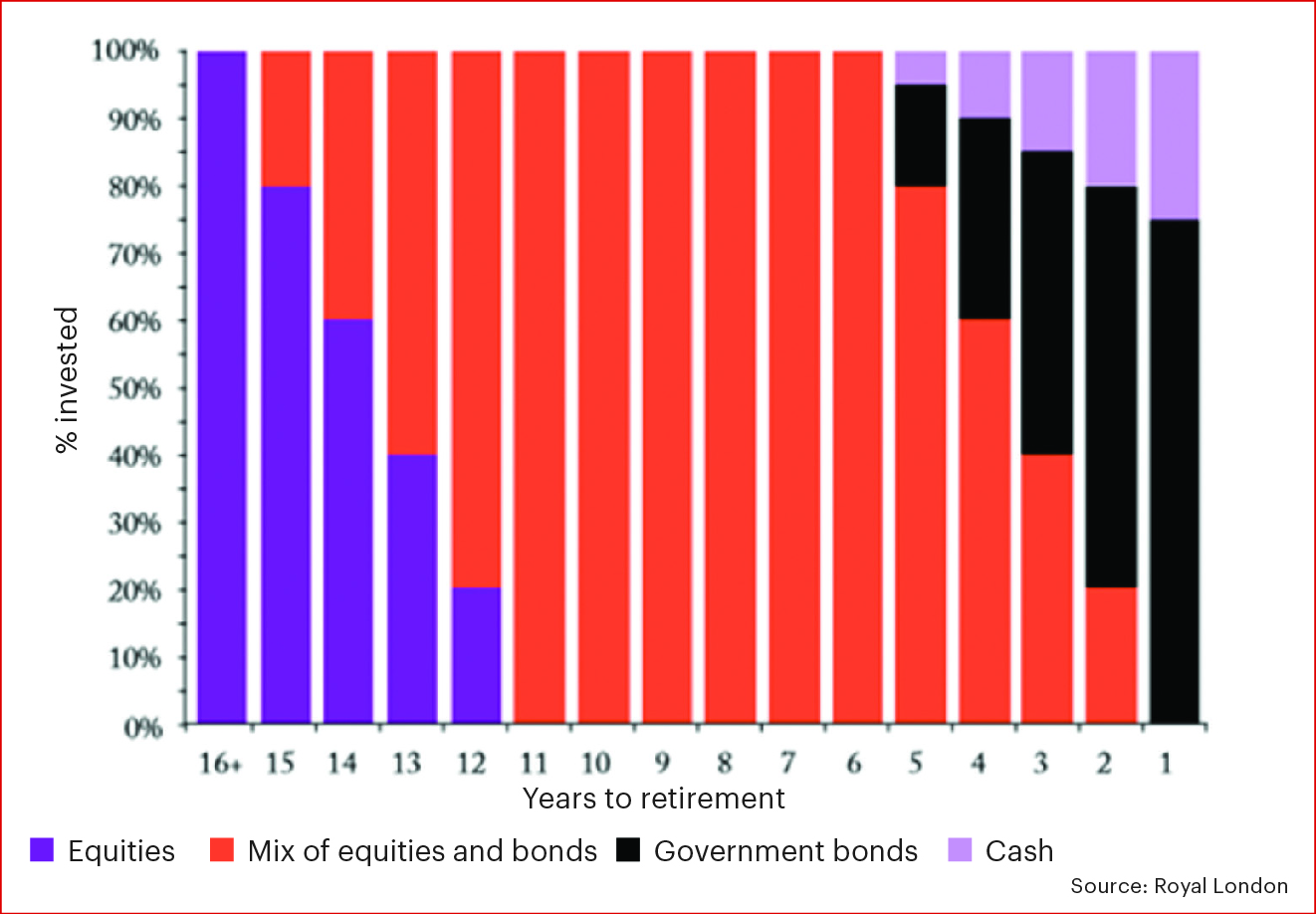

‘Lifestyle’ (or ‘target date’) investment products systematically shift your investments over time as you get older or near retirement date. They were designed to help investors benefit from stock market growth in the early and middle part of their career whilst protecting them from the risk of losing money in case of a stock market crash just before retirement.

Chart one, below, shows typical examples of the asset allocation changes of a lifestyle fund, whereby the ‘risky assets’ (shown in purple and red) are gradually replaced with the ‘safe assets’ of cash (mauve) and government bonds (black) by the date of retirement in the far-right column.

This move from relatively risky equities towards low- returning but safer bonds was seen as a great solution, meaning that the investor would be sitting on a nice nest-egg of low-risk government bonds and cash by the time they hold their retirement party.

Originally, the idea was that the nest-egg would be used to buy an annuity to provide an income in retirement, but new pension freedoms and much lower incomes on offer have resulted in plummeting sales of annuities.

These investment products were introduced in the late 1980s but have become particularly prevalent as the number of defined contribution pensions have ballooned, with around 90% of these pensions invested in them.

Risk-less returns?

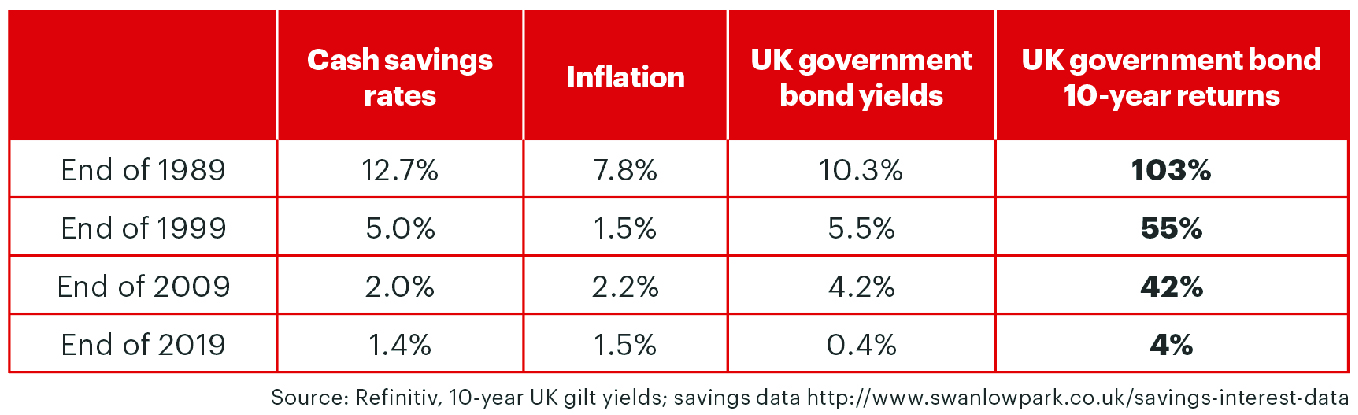

However, markets have moved a long way since the products were launched and the investment world is very different. Let’s have a look at table one to see how the picture has changed at each of the 10-year anniversaries of the products since they began.

The ‘cash savings rates’ column tells us what we all know which is that we now get very little, if any, interest on our savings and invariably less than the inflation rate (shown in the next column). Contrast this with the nearly 13% savings rates received at the end of 1989 and, although the rate of inflation was higher than now at 7.8%, it was substantially less than the savings rate of 12.7%.

Now look at the ‘UK government bond yields’ column – this is the really important bit. Like the savings rates, yields were in excess of 10% in 1990 but now stand at only 0.4%. The final column really underlines these numbers. Essentially, the return from a government bond is its yield – let’s say you buy a 10-year government bond on the day of your retirement and hold it for 10 years – over that time, your return will be 10 times the yield.

Instead of a return of 103% that a retiree could expect in 1989, the return over the 10 years from today is now only 4%! Remember, not only is this figure before any costs and expenses but it’s considerably lower than the current rate of inflation of 1.5%, leaving the investor significantly worse off in real terms.

Indeed, a £1m pension pot in a portfolio comprising 80% government bonds and 20% cash when lifestyle products were launched in 1990 could have provided an annual income (pre- costs) somewhere in the region of £108,000. Today, that would be down to a mere £6,000.

This is a very real problem. Worse, bond yields could easily fall even further and potentially, like European government bonds, go negative – your pension pot could end up paying out interest, rather than receiving income.

Chart one: Typical asset allocation changes of a lifestyle fund

Table one: Products at 10-year anniversaries

Return-less risk?

The other reason that ‘lifestyle products’ gradually shifted to government bonds and cash was that they were considered very low risk. Whilst there is still negligible risk of a UK government or bank going bust, capital risks have become more acute for holders of government bonds because bond ‘duration’ is much higher. ‘Bond duration’ is simply the sensitivity of a bond to interest rates. In 1990, the duration on 10-year government bonds was 6.5%, which meant that if interest rates increased by 1%, the bond (because of the inverse relationship between a bond price and its yield) would lose 6.5% in value. Whilst painful, this was more than offset by the 10.3% pa income the investor was receiving (giving a 10.3% – 6.5% = 3.8% total return).

Your pension pot could end up paying out interest

Today, the same government bond would lose the investor much more – 10%. And, the much lower 0.4% income would mean a straightforward total return loss of around 9.6%.

So, aside from the fact that lifestyle products invest blindly without regard to individual circumstances and the dangers of inflation eating away the real value of the returns, there is also the large and tangible risk of capital loss.

If you are an investor, what can you do?

If you are still more than 10 years from the target retirement date, your portfolio will probably not have started moving significantly into government bonds, but you should consider different investment options.

However, do not wait to be contacted by your pension provider; in 2017, the industry regulator (the Financial Conduct Authority) looked into the providers of these products and concluded, “We are concerned, however, that some firms claim they have little or no responsibility for such strategies and have no plans to proactively communicate with third parties.”

Speak to your adviser to explore solutions – the danger with faulty autopilots is in doing nothing.