In particular, we’re looking at the Tesco 5.5% 2035 bond.

Here are some of the key facts of this bond:

- It was issued in February 2023 and will mature in February 2035 (12-year term).

- Each bond was issued at £100 and will mature at £100 in February 2035.

- At outset it paid a coupon of 5.5% p.a., which is a fixed interest payment of £5.50 per bond per year.

- Tesco is BBB rated.

Whilst it was only issued in February (approximately 6 months ago), interest rates have moved higher than expected. As a result, to remain attractive, the bond has fallen in price. Here are some of the characteristics now:

- There is roughly 11.5 years to maturity.

- The price has fallen to £93.

- The £5.50 coupon is now 5.9% of the current price (running yield).

- If held to maturity, investors will also make a £7 capital gain (as price goes from £93 back to £100).

- The current yield to maturity is 6.25% p.a. – this is the total annualised return if held to maturity including all income payments and the capital gain.

Imagine a £10,000 investment…

Let’s assume you had invested £10,000 into this bond when it was issued.

- If you had invested £10,000, it would now be worth only £9,300 (£700 loss).

- But if you hold to maturity, you will make a £700 gain (7.5%).

- Add the coupons of £550 p.a. x 11.5 = £6,325 income.

- Total return if held to maturity would therefore be £7,025 = 75% (6.25% p.a.).

What are the risks?

Whilst we know what return we will get if we hold to maturity, this return is unlikely to come in a “straight line.”

Let’s assume Tesco is unlikely to go bust during this period. Therefore, the main risk to this bond is if interest rates go up further than expected. If so, the price might fall further.

Let’s assume investors want an additional 1% p.a., so the yield needs to increase from 6.25% p.a. to 7.25% p.a.

Because we know all the cash flows of this bond, we can calculate what will happen to the price in this scenario.

The bond would have to drop a further 8.26% in price to increase the yield to maturity by 1% p.a.

In this example, the price would drop to c.£85.30 so our £10,000 investment would now be worth £8,530 – a further loss of £1,470.

This would be quite painful in the short term, but don’t forget we’re still receiving annual income payments of £550 on our £10,000 investment.

This will cushion the blow and in fact over 1.5 years we would receive more income (£1,650) than this loss (£1,470).

And don’t forget, we will still get back £10,000 at maturity, so the capital value should gradually appreciate as the term goes on. We just need to be patient.

Summary

We think corporate bonds look quite attractive, because even fairly secure companies, like Tesco, are paying yields in excess of 6% p.a.

If interest rates go up further than expected, in the short term we might see further capital losses, but these would likely be relatively temporary in nature.

Don’t forget that if rates don’t go up as much as expected, or are even cut, then the opposite could happen, and we could get a capital gain in the short term too.

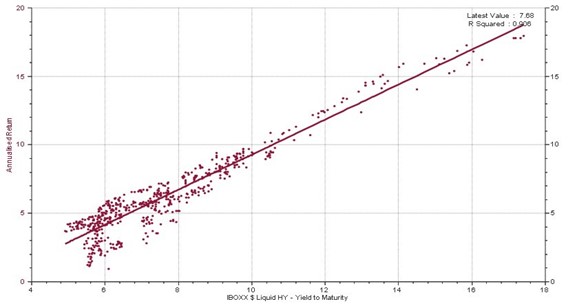

We also invest in high-yield bonds, where companies have lower credit ratings. On the funds we hold, the yield to maturity of these bonds is around 10% p.a. (Source: EIM / the various fund managers, 30 May 2023)

For more detail of how high-yield bonds work, and the risks involved, please read the next section.