Executive summary:

- Early Budget speculation reflects heightened political and economic sensitivity, with Rachel Reeves facing a constrained fiscal landscape and limited room for manoeuvre.

- Investor interest is intensifying, as short-term policy signals and spending decisions could have longer-term implications for markets and confidence.

- The UK’s economic outlook remains uncertain, with debates around industrial strategy and public spending revealing deeper concerns about resilience and growth.

- Global context matters, as countries increasingly adopt joined-up strategies in response to a more polarised world – influencing how the UK positions itself economically and politically.

Politics and productivity

Rachel Reeves is not delivering her next Budget until 26 November, but speculation as to what it might contain is already well under way!

There have already been plenty of rumours of potential tax changes. Most of this is pure speculation at present. Our financial planners will deal with any tax changes as and when they occur, and we’ll of course be in touch if it might affect you once we have the details.

Why so much speculation, and how come it’s started so early? And what does this tell us about the UK economy and the implications for investors?

A major reason for all the debate is that Rachel Reeves has only a very narrow path she can follow. Partly that’s down to markets, partly it’s down to the UK’s Budget process, but largely it’s down to the constraints that Reeves has set herself!

These constraints are a mixture of manifesto pledges, and the fiscal rules the Labour party has imposed on themselves.

In their manifesto, Labour pledged not to increase income tax, National Insurance on individuals, VAT or corporation tax. Together, these taxes account for about 2/3rds of the government’s revenue (Source: Institute of Fiscal Studies).

The fiscal rules they’ve set themselves include a commitment that day-to-day spending must be covered by revenue (not debt), and that government debt must be falling by the end of the parliament, relative to the size of the economy (as measured by Gross Domestic Product, GDP).

At every budget, the independent Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) produces a set of analysis and forecasts. This includes forecasts for government debt going well into the future.

This forecast could have significant implications for short-term government policy. If they forecast that the government is on track to meet the pledge for the debt to GDP ratio to be falling, then Reeves won’t have to raise taxes or cut spending.

If they forecast that the government might miss this target, perhaps because the economy is not expected to grow as much as expected, or because borrowing is expected to be higher, then the Chancellor will have to do something about it or break some of the government’s promises.

Some might argue it would be more sensible to take a long-term view and not keep adjusting policy based on changes in long-term growth assumption. However, because of the Budget process and the rules she’s set herself, this doesn’t appear to be an option for the Chancellor.

This means that if the OBR produces a disappointing growth forecast (for example), then Reeves might be forced to cut spending or raise taxes.

If she is not to break manifesto promises, then any tax rises are likely to focus on things like capital gains tax, inheritance tax, or perhaps even council tax. This is the source of the speculation and perhaps even a source of worry for clients. However, it should be emphasised that we don’t know what tax changes she will make, and she may not even make any at all!

Productivity puzzle

Reeves might instead try and rein in spending to stay on track, but here again, she has to be careful.

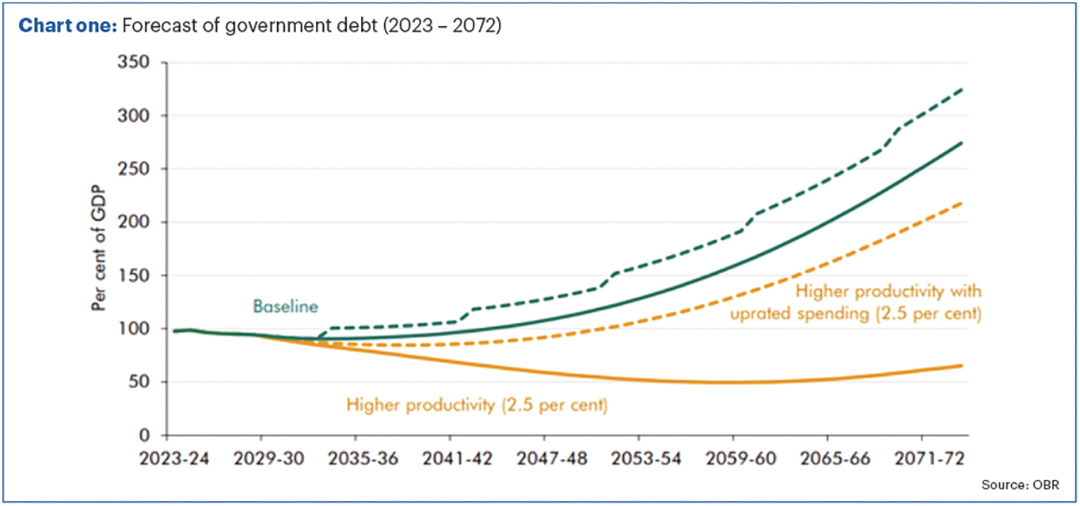

Chart one produced by the OBR in March this year, illustrates both the problem about government debt, and highlights how we might go about tackling it.

The thick green line shows their central forecast. Currently standing at around 100% of GDP, government debt is forecast to fall over the next decade or so (meeting the fiscal rules). But then it begins to increase again as our ageing population leads to higher spending on things like pensions and health.

By the 2050s, it is forecast to reach 150% of GDP, and over 250% by 2070!

However, the chart also hints at the potential solution. If the economy grows faster, then even if the size of the debt grows in nominal terms, the proportion relative to the size of the economy won’t grow so quickly. One way we might be able to get higher growth, is if we become more productive.

The solid yellow line shows what would happen IF we could increase productivity growth from the OBR’s current forecast of 1.5% p.a. to 2.5% p.a. This means debt would actually continue to fall relative to GDP.

In other words, if we can increase productivity sufficiently, then the Chancellor’s problem might go away! For context, however, we have not had annual productivity gains of over 2% since the 1990s and in recent years, has generally been below 1%.

Investing in the future

So how do we do become more productive?

Well, Artificial Intelligence (AI) could help here, but the long-term impact is highly uncertain.

Whilst big cuts to government spending might help hit the short-term deficit target, if not done carefully, it could also reduce economic growth.

Interestingly, the OBR calculated that the increased spending since Labour took office, which includes pay rises for public sector workers, amounted to a stimulus of about 1% of GDP (Source: FT / OBR) – the economy grew more quickly as a result.

Targeted spending can reduce debt over the long term, and the government has set out a number of ways to try and enhance productivity.

This includes investments in infrastructure and green energy, and changes to planning regulation to try and get projects completed faster. These are important, as such projects have been shown to have a big “multiplier effect” – which means you tend to get back much more than you put in.

Government backing in such areas also makes it more attractive for private sector investors, with the Financial Times recently reporting that infrastructure financing in the UK is set for a record year.

We would like to see more targeted investment spending and productivity enhancing measures in the Budget. There’s also been growing discussion around adopting a more joined-up industrial strategy – something many countries are exploring in response to an increasingly polarised global landscape.

For example, Germany has put in measures to support car makers, while the US is supporting (and even taking stakes in) its semiconductor industry. Might we see something similar in the UK? Again, such initiatives can bring opportunities for investors.

Borrowing costs

A linked issue is that the long-term borrowing costs for the government keep increasing.

Recently, the yield (the interest rate the government pays on its debt) for a 30-year gilt reached a 27-year high of 5.69% p.a. This has led to all sorts of headlines about the UK needing an IMF bailout. This is frankly ridiculous, with the most recent sale of gilts by the government being more than 10 times oversubscribed!

It’s also worth pointing out that the increase in borrowing costs is a global issue. Yields have been rising on long-dated government debt around the world, with Japanese 30-year debt recently hitting a record high (records begin in 1999) and with US 30-year yields reaching the highest level since 2007 at the same time (Source: Financial Times).

But the most important aspect is to do with demographics. Most developed countries have ageing populations, meaning that over time governments are predicted to have to spend more on health care and pensions, with fewer workers to pay taxes.

The UK is therefore far from being the only country predicted to see a big increase in debt levels. The US is also likely to hit 150% debt to GDP ratio in the 2050s, but this isn’t a patch on Japan where it’s already 234% of GDP! (Interestingly Japan is still able to borrow money at low rates).

In essence, there is likely to be a greater supply of bonds in the future. In the UK, there is also less demand from pension funds, who have historically been one of the biggest buyers of gilts. As final salary pension schemes close, the number of gilts required to match pension liabilities reduces. Demand has also reduced now the Bank of England has essentially put Quantitative Easing (QE) into reverse and are selling some of the bonds they bought a few years ago.

More supply and less demand reduces gilt prices, and therefore (given the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields) leads to higher yields.

Longer term, this could cause an issue for governments, with higher interest costs making those deficit issues worse. As a result, we expect they may focus on issuing shorter-term bonds to try and reduce this impact.

Whilst we invest in a lot of bonds in portfolios, it should be emphasised that higher yields might not be good for the government, but it also means we get paid more for lending to them!

Despite this, we mainly prefer lending to companies rather than governments where we get paid a higher yield and prefer shorter-dated bonds to longer-dated ones, where some of the risks outlined are much lower.

Last Autumn, Rachel Reeves described her Budget as a one-off “reset”, stating she did not expect to have to make further major changes across the course of the Parliament.

Constant changes to tax can itself have an impact on growth, with companies and individuals holding off on investments until there is more clarity. We would therefore urge continuity, and a focus on growth and productivity enhancements.

Past performance is for illustrative purposes only and cannot be guaranteed to apply in the future.

This newsletter is intended as an information piece and does not constitute investment advice.

If you have any further questions, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us on 0161 486 2250 or reach out to your usual Equilibrium contact and we can help to maximise your entitlements.

New to Equilibrium? Call 0161 383 3335 for a free, no-obligation chat or contact us here.