Executive summary

- Stock market bubble concerns: Media headlines are questioning whether we’re in a stock market bubble, particularly in US tech stocks linked to artificial intelligence.

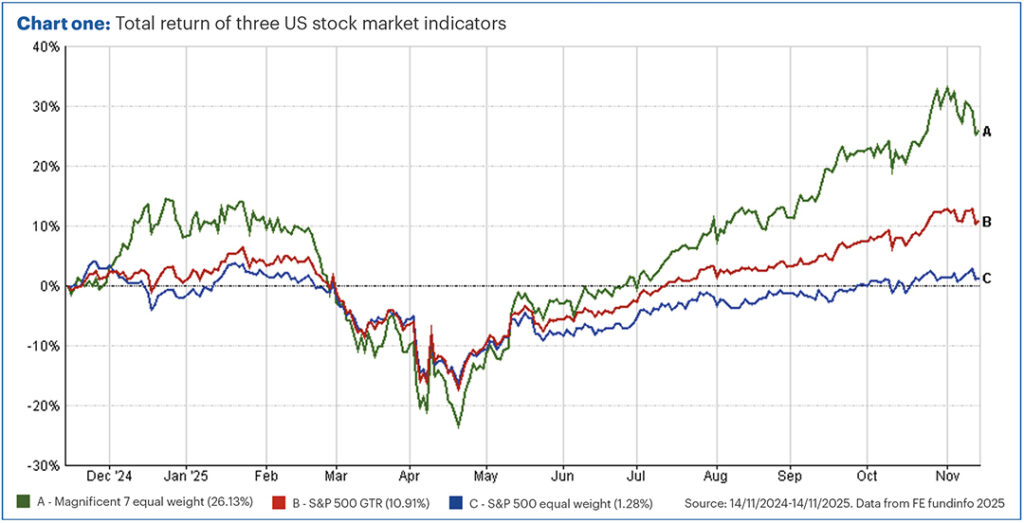

- Performance disparity: Over the past 12 months, the S&P 500 (market-cap-weighted) rose nearly 11%, while an equal-weighted version of the same index gained only 1.3%, highlighting the dominance of large-cap companies.

- Tech giants surge: The “Magnificent Seven” tech stocks (Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla) delivered a 28% return, with Nvidia surpassing $5 trillion in market value and becoming the world’s largest company.

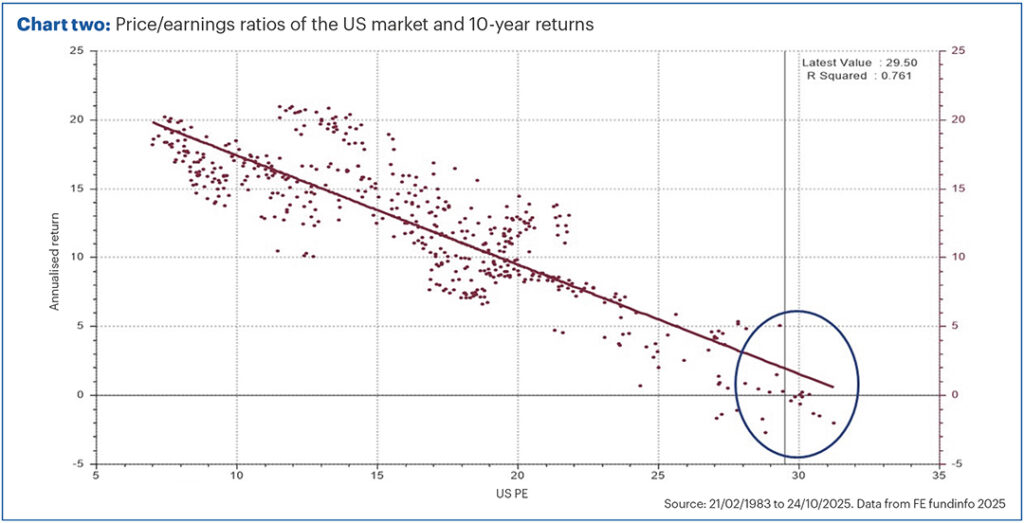

- Valuation concerns: The US market’s price-to-earnings ratio is near 30 times profits, significantly above historical norms, fuelling fears of overvaluation.

We have recently seen several newspaper headlines asking: “Are we in a stock market bubble?”

In fact, I’d go so far as saying there seems to be a bubble in people asking if there’s a bubble!

In particular, people are worried about a potential bubble in US tech stocks, related to artificial intelligence.

It is true that the big tech stocks are doing far better than the rest of the market as we have looked at before.

Chart one shows the total return of three US stock market indicators over the past 12 months. The red line is the main US market – the S&P 500 Index. This is the index of the 500 largest companies on the US market and is “market cap weighted” which means that the bigger companies have a bigger weighting in the index. This is up just shy of 11% over 12 months.

The blue line is the same 500 companies, but with them all equally weighted. The average stock in the index is up just 1.3%. This tells us the big companies are doing much better than the average!

The green line is the so-called “Magnificent Seven” big tech stocks (an equal weight portfolio of Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla). This is up 28% over the same period.

In particular, Nvidia (who make the powerful microchips needed to power AI) are doing phenomenally well, becoming the world’s biggest company and recently surpassing the $5 trillion mark!

The significant outperformance of tech stocks is one reason why people are concerned about a bubble. The second is valuation, something we talk about all the time. You can skip this bit if you’ve heard it before!

The price/earnings ratio of the US market is close to 30 times the profits being made by the companies. This is very high compared to history.

As we often point out, valuation indicators often correlate well with long-term future returns (but don’t help in the short term). Chart two shows how the price/earnings ratio of the US market has correlated to 10-year returns in the past.

Each dot is a different 10-year period for the US stock market in history. The higher the dot, the higher the return was over that particular decade. Across the horizontal axis is the price/earnings ratio at the beginning of the 10 years. Generally, you end up with a high return when the ratio was low at the start, and a low return when it was high.

I’ve circled all the times in the past when the ratio has been around the 30 times mark. Typically, you’ve ended up with very little return, and a range of outcomes from a small loss to around 5% p.a.

This tells us we might want to be slightly cautious about how much we allocate to the US. We might prefer to allocate more elsewhere where markets look better value in our view.

However, is that the same as saying there is a bubble? And will that bubble burst any time soon?

What is a bubble?

According to Google’s Gemini AI:

“A bubble is a period where asset prices, like stocks or real estate, rise rapidly far above their fundamental, or intrinsic, value. This is driven by speculation, herd behaviour, and the expectation of future price increases, creating a self-reinforcing cycle until the bubble inevitably bursts, leading to a sharp price decline.”

Whilst US stocks look expensive relative to history, are they far above their “intrinsic value”? This is difficult to assess, since it depends partly on how quickly US companies can grow in the future. If their profits grow very quickly, then the high price/earnings ratio might be justified. We can’t know for certain in advance.

So, is there excessive “speculation, herd behaviour, and the expectation of future price increases”? Again, there is certainly an element of that, but also the number of people expressing worries about a bubble show that sentiment isn’t at the euphoric “we can’t lose!” stage at present.

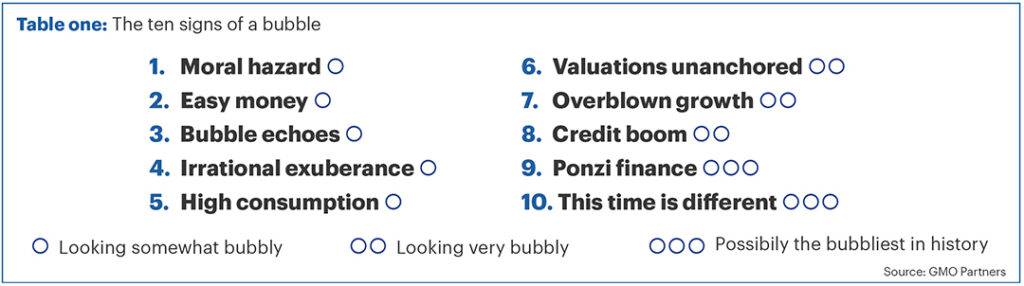

According to Edward Chancellor (who has written books on financial speculation) of GMO Partners, there are ten signs that a bubble might be breaking out. Table one shows GMO’s current assessment of each:

According to GMO, most of the indicators are only “somewhat bubbly”, with valuations merely getting into the “looking very bubbly” camp. However, of more concern is the narrative of “this time is different” which has gained a lot of traction, and there are definitely a few red flags around “Ponzi finance”!1

We’d mainly agree with this assessment – some of the conditions for a bubble are met but some are probably not there – yet!

Financing the future

The big tech companies are clearly making superior profits to most other companies, and these profits are generally growing faster than in other industries. In that sense, their outperformance is justified and may continue for some time.

Our primary concern, along with GMO, centres on what GMO refers to as “Ponzi finance” and the potential consequences this may present for the future.

In order for the tech companies to continue developing and enhancing AI, they are investing huge amounts of money in the future.

In particular, they are spending a lot of money on data centres – big buildings full of computer servers – all with the latest and most powerful (usually Nvidia) processors. It is estimated this is running at between $450 and $600 billion a year. (These centres also need a huge amount of electricity – some of the figures are astonishing, but perhaps something to discuss another time!) As we looked at in our recent quarterly report here, all of this spending is driving the US economy, which would have barely grown this year without it.

One concern is whether all this spending can be sustained. Might the companies build too much capacity and could some of this investment be wasted? What happens when those companies stop investing so much? What impact will this have on the US economy? How would this affect companies like Nvidia, if the other big tech companies no longer need so many chips?

Another concern is that a lot of this spending is in some ways “circular” (which is where the Ponzi description comes into play).

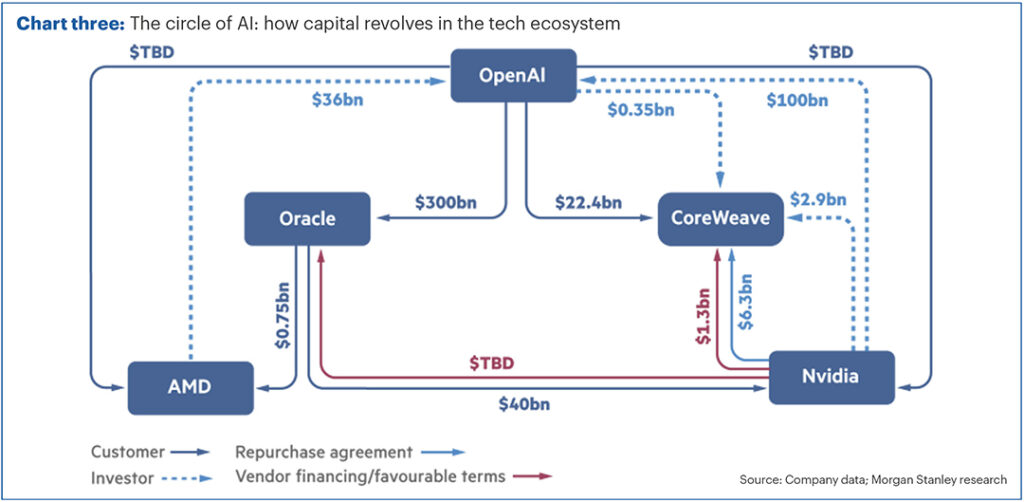

This is illustrated neatly by Chart three from the Financial Times, which looks at the relationship between OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT) and some of the other tech firms.

OpenAI have made a lot of commitment about future spending. In total, those commitments add up to about $1.5 trillion!

However, at present OpenAI only makes about $14 billion a year in revenue from what we can tell (as a private company, there’s little data available). There’s a lot of growth (or a lot of debt) required in order to meet those spending plans!

But in return for these commitments, some of the other tech firms have also committed to investing in OpenAI.

For example, Nvidia recently announced it would invest up to $100 billion in OpenAI’s stock, making it a significant shareholder. In return, OpenAI will buy millions of Nvidia’s processors.

This might be viewed as Nvidia helping to fund their own sales.

And as Chart three shows, this is far from the only such investment, with similar arrangements being made with other hardware providers.

This might all be fine, but the problem with such a circular trend is if one part breaks down – say OpenAI are unable to monetise their service, turning users into paid subscribers, they might not be able to buy all the chips they say they will!

Debt demand

The final area of concern is around the debts required to finance all this spending.

To date, most of the spending from the big tech firms has been funded from their large profits. These firms are very cash generative and have at times been sitting on huge amounts of money in the bank.

However, the sums for future spending are so vast these reserves are no longer going to be enough. According to Bank of America, the big tech firms borrowed about $75bn in September and October alone, with Meta responsible for $30bn of this debt issuance.

Some investors didn’t like this announcement, and Meta shares sold off sharply.

If the big tech companies are no longer going to be sitting on vast cash reserves, but instead will be much more indebted, this is a big change which (amongst other things) makes them riskier investments.

If the AI opportunity is as large as many people think, then this might all be fine. However, with such vast sums being spent for so long, the risk of missteps increases.

On balance, we don’t think the US stock market is in a bubble today. We think it’s expensive and that warrants some caution, but we remain invested. We just try to be creative about how we invest, and in some portfolios try and “hedge” our positions by also holding other assets we think could cushion the blow if stocks fall.

However, we do worry that the current growth rate cannot be sustained indefinitely, and the longer it continues at this pace the more chance there is of something going wrong in the future.

Past performance is for illustrative purposes only and cannot be guaranteed to apply in the future.

This newsletter is intended as an information piece and does not constitute investment advice.

If you have any further questions, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us on 0161 486 2250 or reach out to your usual Equilibrium contact and we can help to maximise your entitlements. New to Equilibrium? Call 0161 383 3335 for a free, no-obligation chat or contact us here.

1 Ponzi finance is an unsustainable funding structure that inevitably collapses when the flow of money stops.