Executive summary:

- Tariffs are paid by domestic importers, not foreign exporters. These costs are often passed on to consumers through higher prices or absorbed by businesses via reduced margins.

- Recent US tariffs have surged to historic highs, with some reaching 54%, contributing to inflationary pressure and market volatility.

- Strategic responses include front-loading imports, shifting supply chains, and adjusting investment portfolios to mitigate risks.

- We remain cautiously optimistic about the US market, focusing on quality stocks with strong earnings and low debt, while also using defined return plans and a put option as portfolio insurance.

Who pays the tariffs?

Let’s get the facts straight. US tariffs are not paid by overseas governments or consumers. They are paid to the US government either directly by US companies that import goods, indirectly through higher prices borne by American consumers, or, to a much lesser extent, by overseas exporters.

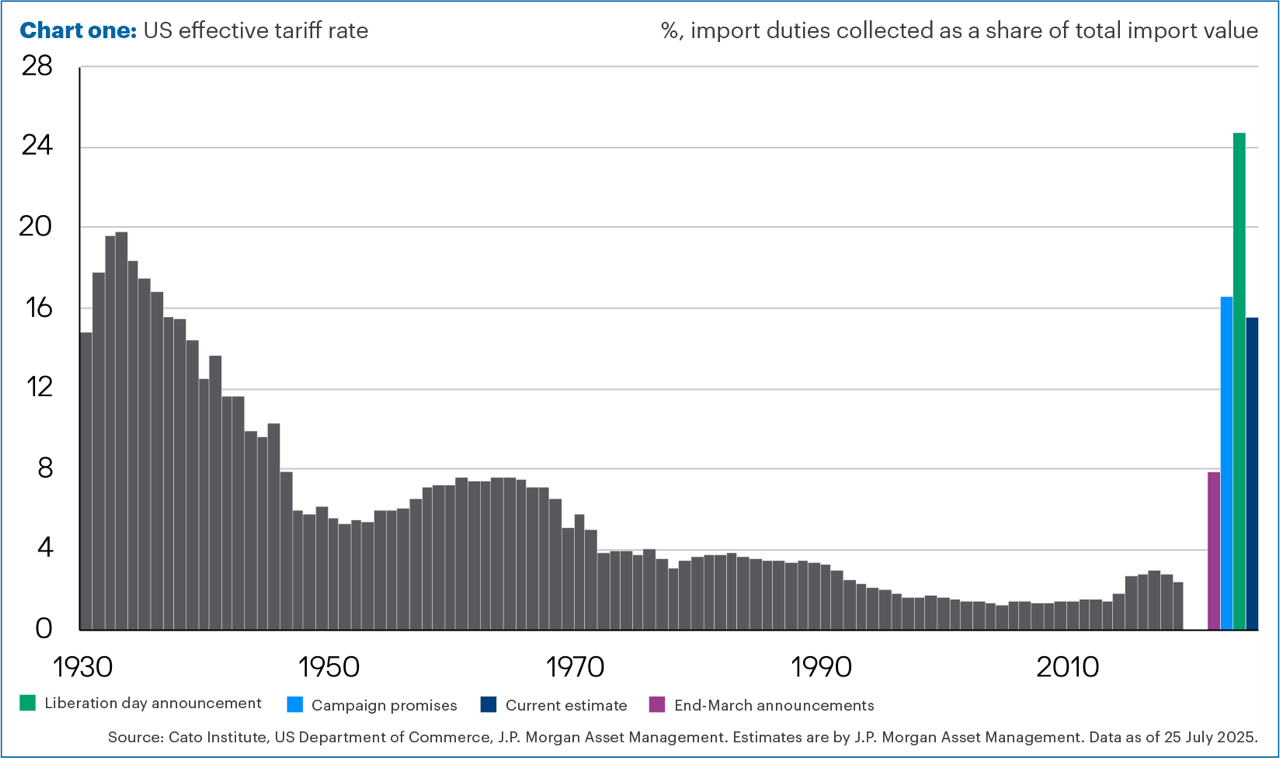

As Chart one shows, the current level of proposed tariffs is at a level not seen since the 1930’s, rising from an average of 2.5% at the end of last year to around 15% today – although this is always subject to change!

Surely, then, someone is going to suffer…are US companies going to have to lower profits or will US consumers see higher inflation?

The answer is yes, but the pain may not be as severe as some predict.

First service

The US consumer buys much more services than manufactured goods. In fact, the ‘goods’ component of inflation is only 18%, yes, less than a fifth – in essence, Joe Public spends much more on their Netflix subscriptions or airfares than physical stuff (by the way, in Japan and the UK, the figure is around 50%).

US import tariffs rose from an average of 2.5% earlier this year to about 15% now. Thus, if consumers shouldered all the extra tariff costs, we see all the additional c.12.5% added to the 18% spent on goods then overall inflation could be 2.3% higher.

Of course, the likes of Netflix and airlines must invest in hardware so there might be an indirect effect on services costs too.

As we have noted before, this will be effectively a one-off (rather than persistent) rise in the inflation rate which would likely unwind after 12 months, assuming tariffs are held at the current rates.

However, price rises are likely to be tempered by companies selling their pre-tariff stock down first and then feeding price rises through gradually, rather than one big price hike to avoid “sticker shock” whereby consumers baulk at notable price increases.

Overall, consumers are unlikely to bear the full brunt of the cost increases. There is another reason – because most companies can afford to pay too.

In good company

US company profits may well choose to pay the tariffs rather than pass them on in higher prices. Why would they do this?

An obvious one would be to hold back price rises to gain competitive advantage. If many companies decide to absorb the costs, a company could lose market share by going it alone with price increases.

However, there are a number of other reasons, chief among them is that they can afford to give their heightened profit margins.

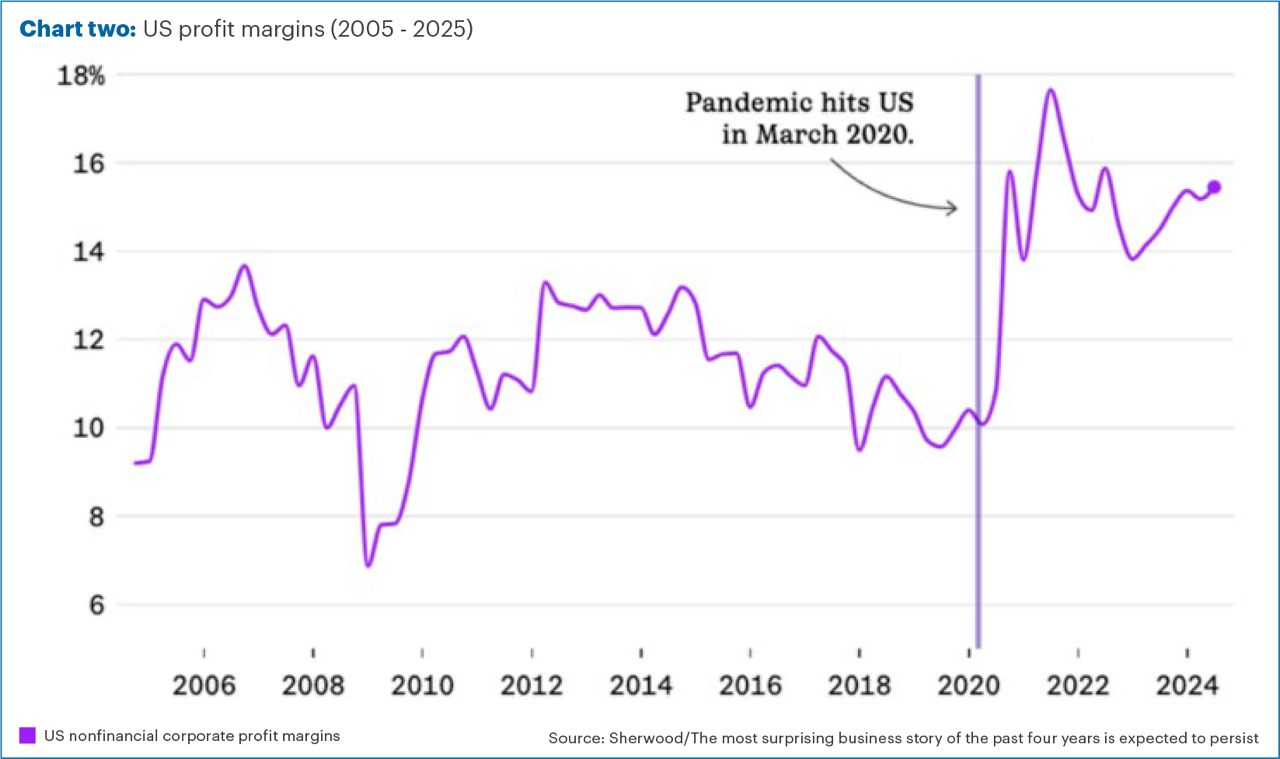

As Chart two shows, profit margins have been relatively strong in the last few years – indeed, they have not been at these levels since the 1950’s. This is not just due to rise of the mega-technology companies, as the margin improvement has been seen across most industries.

In particular, margins have been lifted since Covid, due largely to government fiscal and monetary support such as the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan which injected liquidity directly into businesses, especially small- and medium-sized firms. Equally, interest rates were kept at very low levels after Covid, enabling many to reduce payments and pay down debt. Overall, the Federal Reserve estimates that companies have seen an average margin benefit of 2.5% since Covid. (Source: The Fed – Corporate Profits in the aftermath of COVID-19)

Thus, the payment of tariffs is, in many ways, a way for the government to recoup some of this support, all be it focused on the large international trading companies.

However, it is not all bad news for US companies and there are some positives on the horizon.

Firstly, for companies with overseas sales, the weaker dollar means the translated value of the stronger overseas currencies are positive for profits.

Secondly, part of Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill (BBB), which has now been enacted, allows companies to expense capital expenditure and research and development. What this means is an immediate uplift in return on investment and earnings per share – and thereby a more attractive, lower valuation on the companies’ shares.

In light of this, it is not surprising to learn that, according to Goldman Sachs, as at the end of June, US businesses had paid 64% of total tariff costs, US consumers paid 22% and just 14% by foreign exporters into the US.

However, it is still early days, and these proportions are likely to shift. Forecasters at the Federal Reserve expect that ultimately around half of all additional tariffs will be paid by consumers, around 40% by companies and 10% by foreign exporters to the US.

No AI in tariff

What does this mean for the US stock market? Well, it may not actually be as bad as you might think.

Why? Because, if many tariffs are not passed on in prices, then the inflation effect could be muted, potentially allowing interest rates to be lowered – a positive for markets.

Secondly, profits may be lower than they would have been, but the BBB and weak dollar will mitigate some of this margin squeeze.

Thirdly, it’s worth remembering that the stock market is not the economy. Only around 20% of the US stock market are companies that trade physical goods. Conversely, around 40% of the stock market are technology companies – despite that fact that the technology sector accounts for 9.2% of US GDP this year. (Source: Forrester forecasts/US Tech Spending Forecast To Hit $2.7 Trillion in 2025)

As a result, services and in particular the higher growth technological services are far more important to the performance of the US stock market than manufacturers of goods. In 2024, for instance, the US stock market returned 25% with technology stocks contributing nearly half of this return – without technology stocks, the market return would have been just 11%! (Source: Statista/Chart: AI-Powered Tech Boom Fuels 2024 Stock Market Rally)

The market’s focus is much more on the progress in artificial intelligence (AI) and the potential returns for the technology companies as spending in this area ramps up. AI stocks alone are estimated to have driven 60% of the return of the US stock market so far this year. (Source: Datatrek Research)

The fox and the goose

The bigger issue for investors in the US market is that the valuations are historically very high. Trump’s erratic approach of imposing tariffs on countries, sectors, industries or even individual companies (and berating certain business leaders) adds an extra element of risk to a market that is priced for expectations of high, growing and persistent profitability. If Trump’s policies start to impinge on the stellar growth in AI and technology in general, the market will have a problem with that.

For now, this seems unlikely as technology is the golden goose laying the golden growth eggs. Indeed, the US Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent (FBI codename: Swamp Fox) has a steady, laissez-faire approach that is seen as market-friendly, providing a guiding hand to the President in preventing excessive market risks arising. It was Bessent that drew Trump’s attention to the very negative reaction to the tariffs in April which lead to the 90-day pause, a reversal that the President blamed on the markets “getting a little bit yippy”.

Seismonomics

Like many investors, we are cautiously optimistic for the US market. High valuations are not necessarily a problem if profits continue to rise ahead of expectations and/or investors are happy to pay higher premiums for growth in a world which is seeing a paucity of growth.

Nevertheless, we recognise that risks could lead to weaker returns. Markets are often unpredictable and don’t react to news as even seasoned experts expect. Dislocations like the tariff negotiations and other shocks can always have second or third-order effects that are difficult to determine until they become apparent.

Within our active US holdings, we are focused on quality stocks which means they have good, sustainable earnings and low or no debt on the balance sheet. We also hold a proportion of our US investments via defined returns plans, which have a degree of capital protection built in.

Finally, we also have a ‘put option’ – which is essentially a form of portfolio insurance as it would rise in value if US stocks were to fall significantly. This insurance is relatively cheap to buy when volatility is as low as it has been lately.

Put together, we think these strategies allow us to benefit from continued US stock market growth but hopefully will ensure we will not suffer quite as much should they drop back.

Whilst we constantly monitor the changes, it does provide some comfort that there are investments in the funds that could cushion the aftershocks.

Past performance is for illustrative purposes only and cannot be guaranteed to apply in the future.

This newsletter is intended as an information piece and does not constitute investment advice.

If you have any further questions, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us on 0161 486 2250 or reach out to your usual Equilibrium contact and we can help to maximise your entitlements.

New to Equilibrium? Call 0161 383 3335 for a free, no-obligation chat or contact us here.