This article is taken from our autumn 2019 edition of Equinox. You can view the full version here.

The wealth of the eight richest billionaires on the planet is equal to that of the 3.8 billion people who make up the poorest half of the planet’s population.

That figure was presented at the start of this year in a report by Oxfam to highlight the growing concentration of wealth in the world. In 2016, it was the 61 richest individuals. Indeed, the report shows that between 2017 and 2018 a new billionaire was created every two days.

More to the point, the report shows the contrast between the 12% increase in the wealth of the very richest last year and the fall of 11% in the wealth of the poorest half of the world’s population. As ever in these debates, questions arise as to what can be done about it.

Oxfam point out that a tax of 1.5% on the wealth of the world’s billionaires today could raise $74bn. This would be enough to fill the annual gaps in funding needed to get every child into school in the poorest 49 countries. They argue that such a tax implemented in 2009 could have saved 23 million lives in the poorest 49 countries by providing them with money to invest in healthcare.

Many other economists and commentators have suggested similar measures to rebalance the wealth within economies. As economist Thomas Piketty demonstrated in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, without government intervention the market economy tends to concentrate wealth in the hands of a small minority, causing inequality to rise.

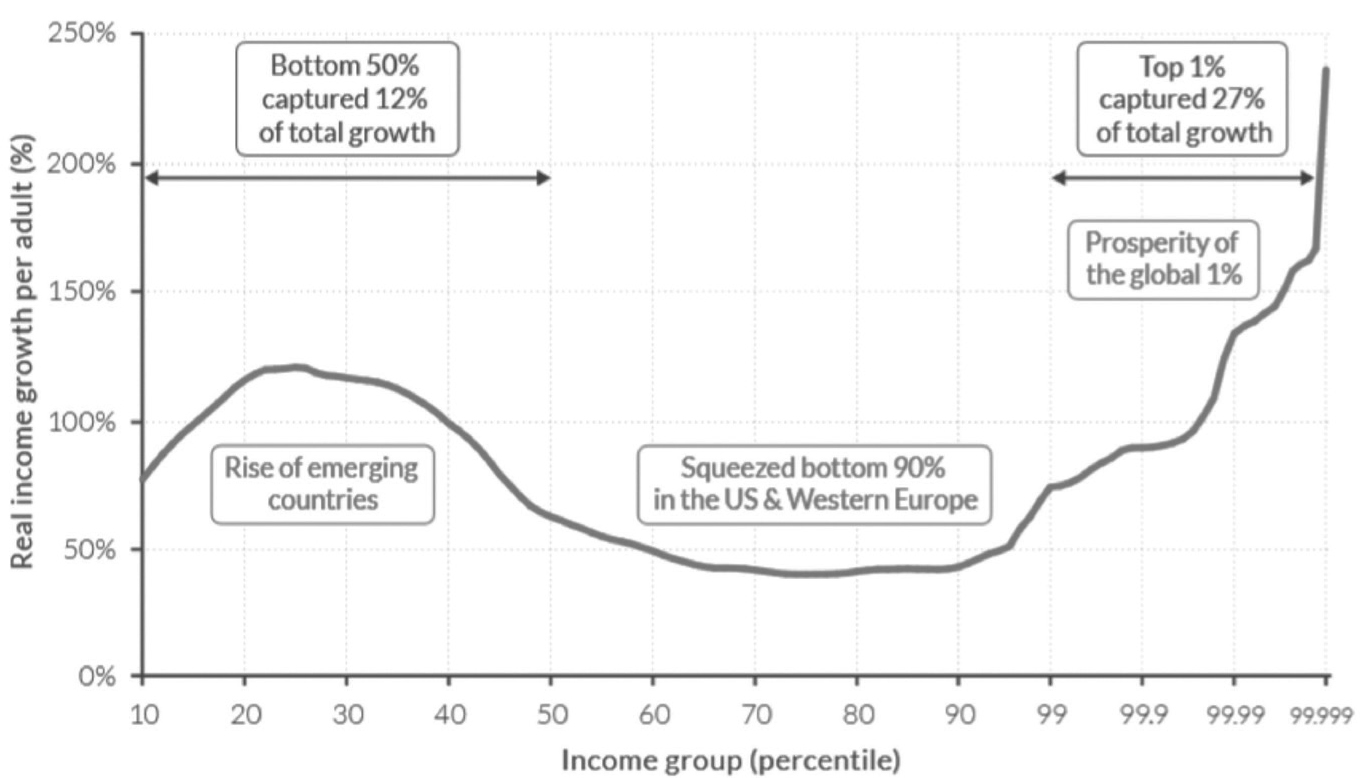

By popular demand Chart one shows how in the 36 years since 1980, real income growth for the top 1% increased by over 200%. Significantly, however, there are large segments of the population – shown as the ‘squeezed bottom’ in the US and Europe – that have seen the lowest real income growth.

It is widely believed that this unequal distribution of wealth within many economies has led to the rise of populism.

The large squeezed portion of the population is seen as the driving force for the emergence of populist political movements. As far as this electorate is concerned, they’re able to register their disapproval by making protest votes to bring in more extreme (and usually more charismatic) politicians to shake things up.

Look at Beppe Grillo, the comedian who co-founded Italy’s anti-establishment Five Star Movement and the success of others such as Boris Johnson, Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands and Mischaël Modrikamen in Belgium.

Pop!

Interestingly, and defying conventional wisdom, research on populist governments so far shows that they are actually effective in wealth re- distribution. Team Populism, a network

of academics, has undertaken detailed analysis to produce the Global Populism Database based on data from 2000 to 2018. The work suggests that, overall, levels of inequality within the respective nations have been reduced to a much greater extent under populists than under other types of governments.

Reflecting the general surprise in the findings, David Doyle, an Associate Professor at Oxford University who headed the research remarked, “This was contrary to what I expected”.

If we accept these findings, then perhaps a solution has been found?

Well, maybe.

Left alone

The trend to populism has resulted in many left-wing political parties being isolated and in much weaker position.

In countries where traditional left-wing voters have been attracted by the policies of the populist right, the left has struggled to counter with effective responses. Populist right-wing parties deliberately target these voters whilst claiming popular support across the political spectrum.

This matters because the emergence of right-wing populist parties brings other narratives that have wider implications. Such parties often have robust policy positions on anti- globalisation and anti-immigration and/or refugee issues. We offer no judgement but merely point to this direction in the political discourse, but clearly such strong views have implications.

Right thinking?

As globalisation has grown rapidly over the last two decades, there has been a significant rise in the movement of goods and people across borders. Yet, given the wide income differentials, developed nations remain attractive for many in emerging markets. This has driven large movements of people, especially from poor and oppressive regimes. Average income level in high- income countries is more than 70 times higher than low-income countries, so it’s unsurprising that many in the developing world opt to try their luck elsewhere.

Many populist governments and movements point the finger at immigration and the perceived threats of an influx of refugees. Headline-grabbing narratives tap into the xenophobic fears of the ‘squeezed bottom’ as these factors are blamed for their economic situation. Thus, international aid becomes a target.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), overseas development assistance to the least- developed countries fell by 3% in real terms from 2017, aid to Africa fell by 4%, and humanitarian aid fell by 8%.

As a government, the US gives less as a percentage of its gross national income than other countries – only 0.17%, well below the 0.3% average for developed countries. However, because the US economy is so large, it still provides more foreign aid in total than any other country, although about 40% of it is considered security assistance, rather than economic or humanitarian aid – but this is changing.

Aid fade

After Congress didn’t back the Trump administration’s cuts to foreign aid in 2017, the administration has been attempting to restructure foreign aid based on its own national interests in a form of quid pro quo in return for foreign policy support.

“Only go to America’s friends,” in the words of President Trump.

The US is not alone. In the UK, a recent report by the National Audit Office highlighted that only 58% of the aid budget was spent in the least developed countries in 2017, with 28% going to lower middle-income countries and 14% going to upper middle-income countries. Indeed, nearly a third of the UK foreign aid budget is now spent by departments other than the Department for International Development, in areas like business and the Foreign Office.

Of course, aid can come in many different forms. The most important form of aid is now in the form of remittances, which is the transfer of money by a foreign worker – usually in an advanced economy – to his or her home country. As Chart two shows, remittances significantly outstrip official development aid (ODA) and foreign direct investment (FDI) as a source of aid.

Global migrant numbers are now at their highest since records started in 1950. The World Bank estimates that there are 266 million migrants (including refugees) which, whilst comprising only about 3.4% of the global population, contribute more than 9% of gross domestic product (GDP).

Chart one

The elephant curve of global inequality and growth, 1980-2016

Reversing the flows

But there’s the rub – the workers that are sending the remittances are the same immigrants in the advanced economies that are the targets of the populist backlash. The danger is that walls are built and immigration gates are closed to reduce the inflow of workers which, combined with the changes in the levels and forms of aid, serves to exacerbate the wealth differences between rich and poor nations. Approval rates for refugee and migrant worker applications are already falling in many developed economies, whilst deportation numbers rise.

Thus the OECD finds that, in addition to the gap between rich and poor countries rising, the gap between the rich and poor within the countries has also been rising.

The long-run increase in income inequality not only raises social and political concerns, but also economic ones. It tends to impede GDP growth due to the rising distance of the less wealthy from the rest of society. Equally, widening gaps between countries can result in civil unrest and failed states that are mired in debt.

The problems that can entail from these widening margins are clear to see. The pressures of greater internal wealth concentration and diverging global wealth will mean many less-developed nations will struggle to pull ahead.

Unfortunately, it’s not as simple as taxing eight individuals.

The good news is that not all of the 2,000 billionaires in the world today are evil robber barons. Ten years ago, a dinner meeting between Microsoft founder Bill Gates and investor Warren Buffett spawned the Giving Pledge programme to persuade their fellow billionaires to pledge at least 50% of their wealth to charity. So far, around $600 billion has been pledged for a wide range of good causes.

Whilst it is not dictated where the pledge is spent (for example, it could simply go to build a new wing at the billionaire’s alma mater) high profile endowments such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation demonstrate the effects of benevolence and global thinking.